The lambs are starting to think they own the place.

Tagged: barn, border leicester, Dorset, ewe, Hollow Oak Farm, lamb, porch, regal, Romney, sheep, taking over, texel

The lambs are starting to think they own the place.

Tagged: barn, border leicester, Dorset, ewe, Hollow Oak Farm, lamb, porch, regal, Romney, sheep, taking over, texel

Today brought another lesson that you can’t get answers to questions you don’t ask. All was quiet during my first sheep check a bit before 6 this morning. Around 7 I went out again and heard the cry of a newborn lamb. On my way out to bring Bravo his breakfast I came up with several explanations for the cry that didn’t involve a newborn lamb (since no lambs were due until the first week of May); then I saw the newborn lamb.

The good news is that Bravo seems to have graduated from eating entire lambs to just snacking on ears. The bad news is that I had a distressed newborn lamb with a missing ear, a hungry guardian dog, and no mother in sight. I put down Bravo’s food to keep him occupied, hustled the lamb into the barnyard, and (of course) called Bill. With his calming influence I was able to do some calendar math and narrow down the candidates for the new mother — one of the Romney lambs I got from Jenny Hughes last fall.

Once I got lamb and mother settled into a jug together in the barn, I talked with Jenny and pieced together what had happened. It seems that Jenny had a fence failure a few days before she brought me the three ewes, and a ram spent a couple of hours with the group of ladies. She didn’t think much of it since the adult ewes had already been bred, and the lambs were barely 6 months old, not likely fertile yet. One of the seven lambs in with the ram that day was in fact fertile, and this morning was 147 days later.

Perhaps the most frustrating part of today’s surprise is that I had most of the flock in the handling system yesterday to vaccinate the ewes I expected to lamb in May. I checked all the sheep for body condition, including the one who gave birth this morning. I noticed that she was nice and big, but I was a little surprised at how thin she was. Bill and I actually spent a few minutes debating whether her thinness might be attributable to lambs getting squeezed out from the hay bale by the bigger, older ewes. Neither of us considered the other obvious explanation — that she was thin because she was too young to be carrying a lamb — since she couldn’t be pregnant. If I’d reached under her, I would have felt the fully-developed udder, but I never thought to ask the question. I’m not sure if I’ve learned this lesson yet.

The other good news is that the lamb seems to be doing well. Once I had lamb and mother in the barn, I milked her a bit and tube-fed the lamb, giving him a bit of energy to start figuring out how to nurse. His ear looked horrible, but it didn’t seem to be bothering him that much.

By evening, the ewe was starting to act like she was acknowledging her lamb, and I had gotten him to nurse a couple of times. With any luck, they will have their collective act together by morning. Bigger questions, like whether the ewe will be permanently stunted by giving birth so young, and why I consistently miss the obvious signs in front of me, can wait for the moment.

By evening, the ewe was starting to act like she was acknowledging her lamb, and I had gotten him to nurse a couple of times. With any luck, they will have their collective act together by morning. Bigger questions, like whether the ewe will be permanently stunted by giving birth so young, and why I consistently miss the obvious signs in front of me, can wait for the moment.

Tagged: bravo, ear, eaten ear, ewe lamb, Hollow Oak Farm, lamb, pasture, spring, unexpected lamb

I went through a phase about a year ago when I was consumed with photographing dried beech leaves still clinging to their branches.

I have a handful of these obsessions, many of which turn into multiyear projects as I struggle to make a photograph that aligns with the image in my mind. Photographing tree bark is another one of my recurring quests, and I’ve come to peace with the thought that I may be working for an audience of one. So as I started to explore the woods at the north end of my farm, I was excited to see that there were lots of beech saplings, just calling out for a photographer to immortalize them.

There’s no buzz-kill like knowledge, though. I’ve been working with a forester, Jeff Snitkin, who’s been patiently teaching me about some of the less-obvious interactions that mold forest ecosystems. One of the first things he pointed out is that the proliferation of American beech saplings is a sign of a forest that’s seriously out of balance. Beech saplings are very tolerant of shade, so they can grow slowly in the forest understory when other trees species can’t get established. They’re also the least-favorite food of deer, so that sprouts and saplings of most other tree species get eaten, leaving the beech without competition. Then when there’s an opening in the forest canopy, from logging or just natural tree fall, the little beeches leap ahead and shade out any remaining competitors.

The wetter parts of my woods are relatively free of beech, both because they haven’t been logged as intensively over the years, and because beech prefers slightly drier conditions.

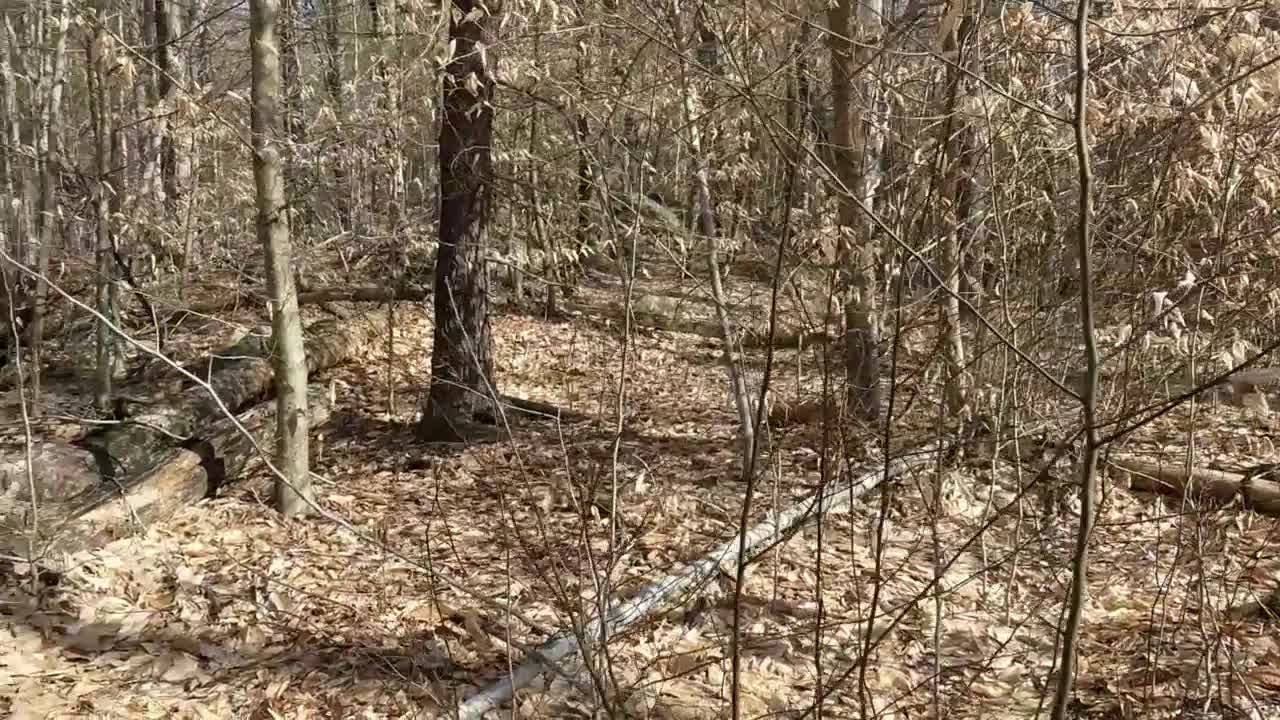

The variety of tree species, dominated by hemlock and yellow birch, and the range of ages of the trees, signal a healthy forest in this section. But much of the higher ground looks like this:

In some spots, the beech saplings dominate the landscape everywhere you look.

Jeff is working with me to develop a forest management plan, and I suspect we’ll spend many hours talking about my beech problem, but I don’t think there are any easy ways to improve the situation. Even if I were inclined to declare total war on the local deer (setting aside my nonexistent hunting skills), my 30 acres of forest is too small a patch to resist regional trends. I’m even less inclined to contemplate the use of herbicides on the sort of scale that would make a dent in the beech population. Jeff has mentioned the possibility of a “reset”, essentially a clear-cut of the forest with careful management of the regrowth, but this vastly exceeds my ambition and my resources, and would leave me with a slowly regenerating wasteland for decades to come. The truth is that I’m too selfish for a solution like this — I want to enjoy my piece of forest, even if it’s ecologically suboptimal.

Tagged: American beech, browse, deer, ecology, Fagus grandifolia, forest, Hollow Oak Farm, monoculture, obsession

Two dogs. Same farm, same activities. One clean, one really not clean. Same roles every day.

Cass refuses to explain.

Tagged: border collies, Cass, Chloe, clean, dirty, Hollow Oak Farm

I’m discovering that farming is a slippery slope. When I bought a string trimmer (weed whacker in the vernacular) a number of years ago, the dealer mentioned that the model I was buying could also be fitted with a rigid blade. My reaction at the time was utter horror at the idea of a large saw blade spinning at the end of a pole that I was holding, but I thanked him for the information. Then last fall I had the Incident with the Rose Bush; I realized that I needed to do something about the multiflora rose thickets proliferating on the farm before they killed all my sheep. I started out attacking the thorned menaces with a set of loppers and heavy gloves, but I soon realized that I would either die of blood loss or old age before I made a dent in the invading roses.

As I plotted and planned over the winter, the spinning blade on the stick started to sound less frightening and more appealing, and today I screwed up my courage and tried it.

This is one of the smaller clumps of multiflora rose, and it was vanquished in an instant.

The catch now is that I don’t have a fancy gas-powered machine that will gather the cut rose stems and move them into a burn pile, so tomorrow I’ll go looking for better gloves, and perhaps a helper.

The catch now is that I don’t have a fancy gas-powered machine that will gather the cut rose stems and move them into a burn pile, so tomorrow I’ll go looking for better gloves, and perhaps a helper.

We’ve just gotten to the point in the year when water no longer freezes hard outside, and this small change has immeasurably improved my daily life at the farm. At some point I hope to have a clever system for providing water to my sheep in the winter, but I didn’t have it this year. My non-clever system was based around 5-gallon jerry cans that I filled with hot water in the bathtub and carried out to the sheep.

The trick was to bring the sheep just the right amount of water that they would drink it all before it froze. Depending on how much snow was on the ground or how thirsty the lambs were for their mothers’ milk, this usually meant 3-4 trips a day with a couple of jerry cans each time. Water, I discovered, is surprisingly heavy*, a fact my back and shoulders will probably remember well into the summer.

Now I’m living the easy life, though. The ewes and lambs in the barnyard have a 50-gallon stock tank that I can fill with a hose from the hydrant at the wood boiler.

It goes very smoothly unless a lamb gets interested.

It goes very smoothly unless a lamb gets interested.

Out in the field, the system is even slicker. The Badger Company, a high-end personal care products manufacturer in the town next door, buys organic olive oil in 1000-litre containers that they only use once; when they’re empty, Badger donates them to local farmers.

The next refinement will be to move the storage tank to the top of the hill, connect it to hoses feeding float valves on the 50-gallon water bowls, and then in principle I’ll have an automatic watering system. To be continued!

___________

*59 pounds each, for the data-driven among my readers.

Tagged: Badger Company, carrying, efficiency, ewes, freezing, heavy, Hollow Oak Farm, lambs, relief, sheep, spring, stock tank, water

Sheep need a source of salt in addition to their grass and water. The local geology doesn’t offer them much, so I provide them with a commercially-prepared mixture of sheep minerals — sodium chloride plus a bunch of trace elements — in a mineral feeder that keeps the salt from turning into a sodden mass when it rains.

The sheep will ignore the minerals for weeks at a time, and then suddenly decide that they have a desperate craving for salt. I have no idea what drives the boom/bust cycle.

The most puzzling part of the whole endeavor, though, is how they manage the geometry of pooping in the feeder.

Tagged: barnyard, ewes, geometry problem, Hollow Oak Farm, lambs, mineral feeder, poop, salt, sheep, sheep minerals

As an experiment, I brought one of the large round bales of fermented hay to the sheep in the barnyard this morning. My motivation was partly self-serving, since putting out 1000lbs of baleage would let me skip bringing small square hay bales to the sheep several times a day, but I also thought (rationalized) that it might benefit the sheep as well. The baleage is both more palatable and more nutritious than dry hay, so I hoped that it might help fatten some of the very thin lactating ewes, getting them to eat a larger quantity of higher-quality food. I also hoped that it would encourage the lambs to eat more grass and nurse less, both speeding their transition to fully-functioning ruminants and easing the caloric burden on their mothers. My biggest concern was that baleage is perishable, and I wasn’t sure if the 8 sheep and 8 lambs would consume it before it started to turn into mush and mold. The sheep and lambs were very enthusiastic about their new grub, but we’ll see how fast they eat it.

One of my other projects today was taking the accumulated farm trash and recycling to the Keene city dump. I was a little taken aback to see that the majority of the load was made up of the plastic bale wrappers that preserve the fermented hay.

In some parts of the country with a higher density of working farms, there are recycling programs for plastic bale wrappings, but here it all goes into the trash stream. I’d like to believe that I can come up with a way to recycle all this shit at some point, but for now I just leave my conscience at the gate and chuck the plastic into the big dumpster at the transfer station.

In some parts of the country with a higher density of working farms, there are recycling programs for plastic bale wrappings, but here it all goes into the trash stream. I’d like to believe that I can come up with a way to recycle all this shit at some point, but for now I just leave my conscience at the gate and chuck the plastic into the big dumpster at the transfer station.

Tagged: baleage, conscience, Hollow Oak Farm, Keene Dump, lambs, nutrition, plastic, sheep, trash, waste

The lambs are picking up pointers from their elders. Bill had suggested that the ramp would become a favorite feature…

Tagged: barn, Hollow Oak Farm, lamb races, lambs, ramp, silliness

This is a dark-eyed junco.

It’s a perfectly nice bird, and it doesn’t at all deserve the feelings I have for it. In Boston, juncos are winter residents, coming south from their more-northerly breeding grounds for the milder winters and plentiful feeders. They start singing their breeding song shortly before they make the return trip north and are usually gone by mid April. The problem is that their disappearance times closely with the due date for personal income tax returns, and they begin singing about a week earlier, as if to taunt the procrastinators in the human populace about the upcoming deadline. I now have to finish my tax preparations by the beginning of March to meet the corporate filing deadline, but I still feel an upwelling of anxiety whenever I hear singing juncos.

It’s a perfectly nice bird, and it doesn’t at all deserve the feelings I have for it. In Boston, juncos are winter residents, coming south from their more-northerly breeding grounds for the milder winters and plentiful feeders. They start singing their breeding song shortly before they make the return trip north and are usually gone by mid April. The problem is that their disappearance times closely with the due date for personal income tax returns, and they begin singing about a week earlier, as if to taunt the procrastinators in the human populace about the upcoming deadline. I now have to finish my tax preparations by the beginning of March to meet the corporate filing deadline, but I still feel an upwelling of anxiety whenever I hear singing juncos.

Tagged: anxiety, Birdsong, breeding song, Dark-eyed junco, IRS, Junco hyemalis, migration, song, tax return, undeserved