I went through a phase about a year ago when I was consumed with photographing dried beech leaves still clinging to their branches.

I have a handful of these obsessions, many of which turn into multiyear projects as I struggle to make a photograph that aligns with the image in my mind. Photographing tree bark is another one of my recurring quests, and I’ve come to peace with the thought that I may be working for an audience of one. So as I started to explore the woods at the north end of my farm, I was excited to see that there were lots of beech saplings, just calling out for a photographer to immortalize them.

There’s no buzz-kill like knowledge, though. I’ve been working with a forester, Jeff Snitkin, who’s been patiently teaching me about some of the less-obvious interactions that mold forest ecosystems. One of the first things he pointed out is that the proliferation of American beech saplings is a sign of a forest that’s seriously out of balance. Beech saplings are very tolerant of shade, so they can grow slowly in the forest understory when other trees species can’t get established. They’re also the least-favorite food of deer, so that sprouts and saplings of most other tree species get eaten, leaving the beech without competition. Then when there’s an opening in the forest canopy, from logging or just natural tree fall, the little beeches leap ahead and shade out any remaining competitors.

The wetter parts of my woods are relatively free of beech, both because they haven’t been logged as intensively over the years, and because beech prefers slightly drier conditions.

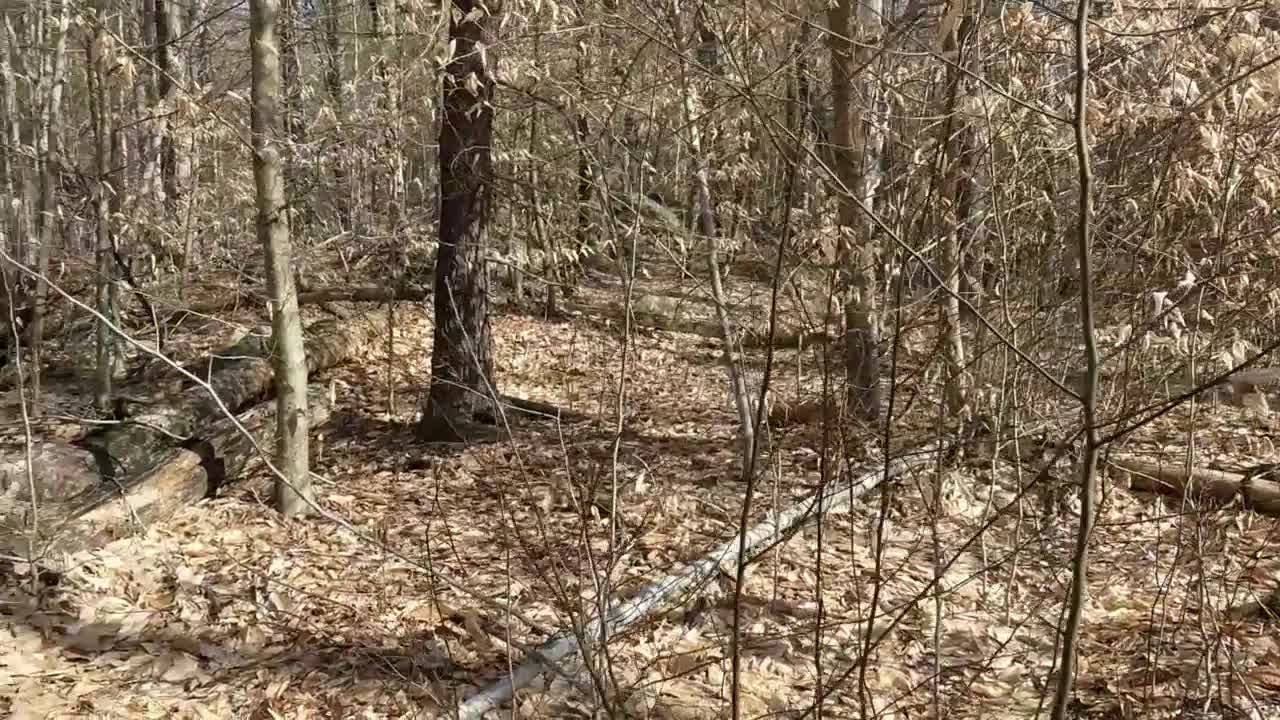

The variety of tree species, dominated by hemlock and yellow birch, and the range of ages of the trees, signal a healthy forest in this section. But much of the higher ground looks like this:

In some spots, the beech saplings dominate the landscape everywhere you look.

Jeff is working with me to develop a forest management plan, and I suspect we’ll spend many hours talking about my beech problem, but I don’t think there are any easy ways to improve the situation. Even if I were inclined to declare total war on the local deer (setting aside my nonexistent hunting skills), my 30 acres of forest is too small a patch to resist regional trends. I’m even less inclined to contemplate the use of herbicides on the sort of scale that would make a dent in the beech population. Jeff has mentioned the possibility of a “reset”, essentially a clear-cut of the forest with careful management of the regrowth, but this vastly exceeds my ambition and my resources, and would leave me with a slowly regenerating wasteland for decades to come. The truth is that I’m too selfish for a solution like this — I want to enjoy my piece of forest, even if it’s ecologically suboptimal.

Tagged: American beech, browse, deer, ecology, Fagus grandifolia, forest, Hollow Oak Farm, monoculture, obsession