Yesterday’s bright light was balanced by gray and rain today. (The ladies wanted to make sure that I understood it was time to move to new grass.)

I was grateful for weather that motivated me to work at my desk most of the day.

Yesterday’s bright light was balanced by gray and rain today. (The ladies wanted to make sure that I understood it was time to move to new grass.)

I was grateful for weather that motivated me to work at my desk most of the day.

The boundary between the grazed and ungrazed sections of the lower pasture caught my eye this afternoon.

Sheep and fence are implied, and the image tells the story of grazing management — uniformly eaten pasture now allowed to rest and recover, with the next paddock awaiting the arrival of the flock. Bill has been preaching the value of short, intensive grazing followed by long recovery, and I’m already seeing the benefits on my fields. Much of the grass around the area is heading into dormancy as November overtakes us, but most of my pastures are lush and green, the grass growing vigorously in response to earlier rounds of grazing this summer.

Tagged: Bill Fosher, boundary, Chloe, fence, grass, lush, management intensive grazing, rotational grazing, sheep

Every time I interact with Bill, I feel like I’ve learned enough since our last meeting to absorb a little more of what he’s teaching me. We’ve talked a lot over the past year about how to read grazing — how to know exactly how big a grazing area the sheep need, and for how long. Early on, he showed me how to look at the grass, how much should be left when I move my flock so that I’m not overgrazing the pasture (“When in doubt, leave more.”). At some point last fall, he showed me how to check the body condition of my sheep, feeling the amount of fat cover on their hips and spine, to get an understanding of their overall health and nutritional status. I try to check body condition once a month to know whether they’re gaining on losing condition the way I’m managing their grazing.

At the Woodbury place, the pastures have been hard for me to judge. They’re full of mature grass that the sheep aren’t so keen to eat, plus a mix of other plants, some yummy and some not; it’s not always been obvious to me whether the sheep have eaten as much as they will or whether I should leave them for a little longer. Bill pointed out that you can tell if a sheep’s rumen is full by looking for a little hollow space in front of the hips. Hollow means that the sheep hasn’t eaten as much as she could in the last 12 hours or so, and it’s completely independent from how much fat cover she has.* If the sheep are looking empty after they’ve been in the grazing area for a while, then they likely need access to more grass — I need to give them a bigger grazing area or move them more frequently. Like many of the things Bill explains to me, this was both revelatory and blindingly obvious (in retrospect), now that I knew enough to appreciate the implications.

On that day, several of my Katahdin ewes were looking particularly hollow, but once I increased the size of their grazing areas, they looked consistently full before I moved them to new grass. This morning I left the flock in the area I’d set for them last night, knowing that they would be a little hungry by the time I moved them, but I wanted to make sure that area got well eaten. Here’s what a slightly empty Katahdin ewe looks like.

Another ewe looks a little empty in this image

but quite full in this one,

so it pays to look carefully. It’s also much easier to judge the state of rumen fill with a hair sheep like a Katahdin. With these gals, who were just shorn in July, it’s already tough to judge hollowness under all the wool.

This latest lesson is giving me additional reasons to keep my Katahdins in the flock. They tend to produce small, slow-growing lambs, but they’re awfully helpful to a new shepherd who’s still figuring out the grazing thing.

_____________

* A fat sheep can have an empty rumen. Body condition is a long-term variable, changing slowly over weeks or months, while rumen fill tells you about the last half day.

Tagged: empty, ewes, full, hair sheep, hollow, hungry, Katahdin, pasture, rotational grazing, rumen, sheep, Woodbury, wool sheep

This is the sheep riot I come home to if I underestimate the size of the flock’s grazing rotation for the day.

Sorry for the shaky video as I walk backwards with hungry sheep bearing down on me….

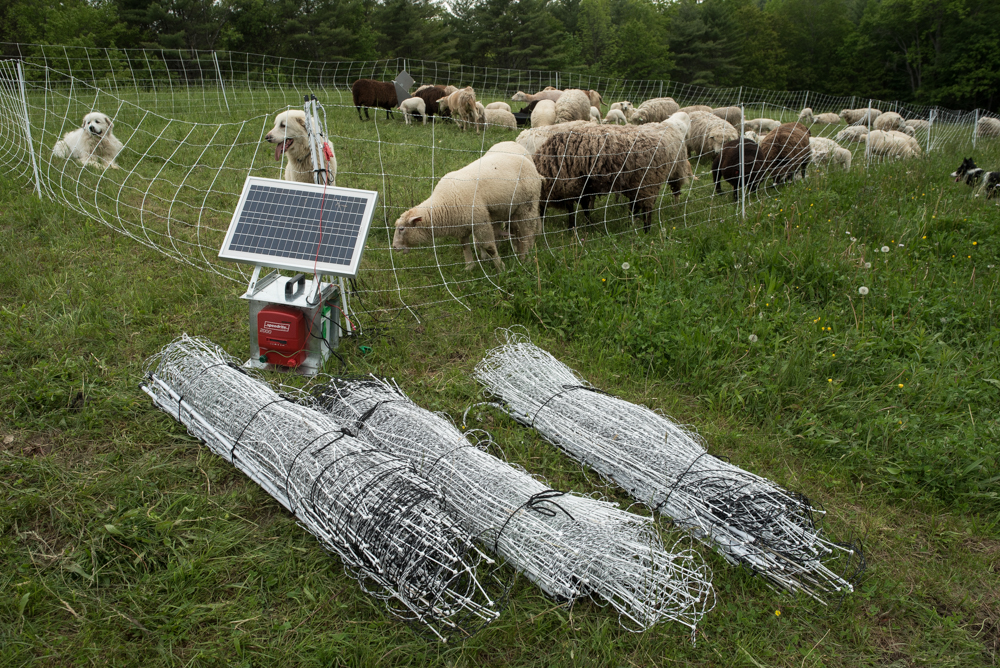

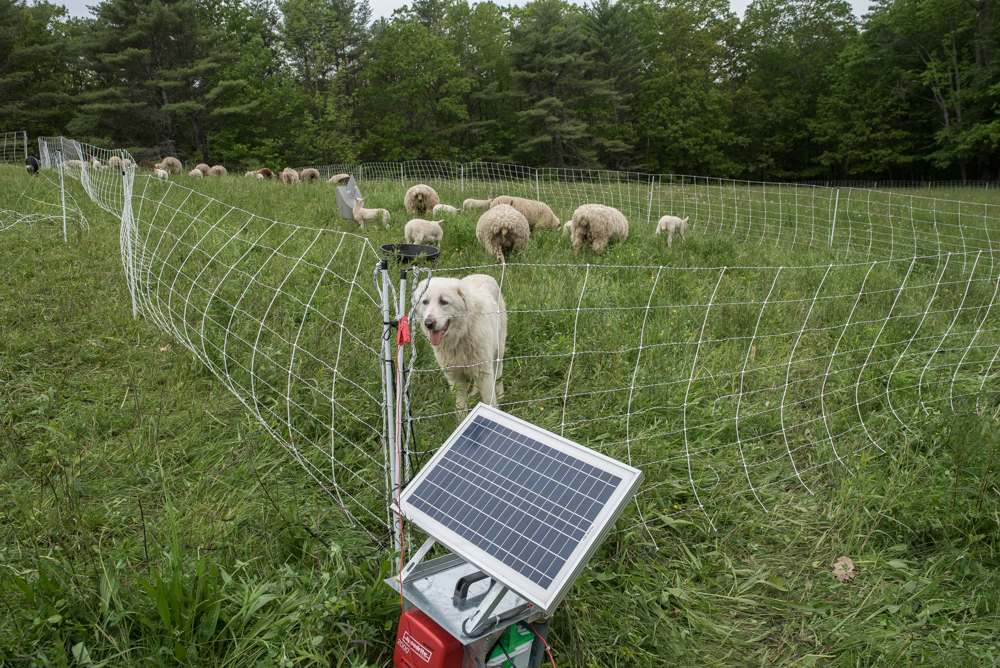

Bill Fosher claims that eventually I’ll develop such muscle memory that electronet leaps unbidden from my arms and sets itself into the ground. I’m not there yet. The portable electric fencing I use to enclose grazing areas for the flock is a crucial part of my operation, but it’s also become my principal preoccupation and adversary. It’s a straightforward enough system: a solar fence charger and rolls of plastic net fencing with stainless steel conductors woven through.

The details, though, reveal that the system was designed by sadists. The rolls of net are sized so that they can be comfortably carried and deployed by someone 6 inches taller and 30% stronger than the one doing the work. The net itself is designed like a ecologically friendly fishing net, allowing squirrels to pass through unimpeded but optimized to snare farmers’ footware. And the fence charger has a handle temptingly located in such a way that no anatomically intact human could use it.

The details, though, reveal that the system was designed by sadists. The rolls of net are sized so that they can be comfortably carried and deployed by someone 6 inches taller and 30% stronger than the one doing the work. The net itself is designed like a ecologically friendly fishing net, allowing squirrels to pass through unimpeded but optimized to snare farmers’ footware. And the fence charger has a handle temptingly located in such a way that no anatomically intact human could use it.

I’ve been setting up big squares of electronet — 164 feet to a side — and then subdividing them into 7 strips, each worth about 12 hours of grazing. This morning I moved the sheep in to the last strip of the previous square, so this evening I needed to set up a new one to start the 3½ day cycle over again. I set up the perimeter first, making sure that my corners all met up before setting the fence upright.

When the big square was complete, I set off the first grazing strip.

When the big square was complete, I set off the first grazing strip.

And then moved the sheep down to the fresh pasture.

And then moved the sheep down to the fresh pasture.

If the sheep eat as much as I expect over night, I’ll move them to the adjacent strip in the morning. Despite my kvetching, I only trip and fall on the net every third or fourth day now. Bill is still much faster than me setting it up, but I’m slowly gaining on him.

If the sheep eat as much as I expect over night, I’ll move them to the adjacent strip in the morning. Despite my kvetching, I only trip and fall on the net every third or fourth day now. Bill is still much faster than me setting it up, but I’m slowly gaining on him.

Tagged: Bill Fosher, bravo, Cass, Chloe, electronet, grazing, pasture, rotational grazing, sadists, sheep, solar energizer, Wellscroft

My daily rhythms with the sheep are now all about grazing rotations — how big an area to give them, how often to move the fence, worrying whether I’m doing it right. The big picture is that sheep consume pasture most efficiently if they’re a little crowded and hungry, so they’re less likely to be picky and instead eat a bit from all of the available plants. Pasture is most productive if it’s grazed uniformly for a short time (ideally before it goes to seed) and then left to recover. The grass is also happier if the sheep don’t eat too much — 6-8″ of remaining leaf height allows it to continue to photosynthesize efficiently and grow back quickly.

My flock of 65 sheep is constant*, but the quality of pasture varies across the farm — some areas support much more plant density than others. So every time I set up a grazing area, I’m trying to figure out how much sheep food it contains and how long the sheep should stay so that they eat just enough but not too much. My goal is to move them twice a day, the sweet spot between efficient grazing and shepherd insanity, according to Bill Fosher. I’m starting to get better at all the necessary guesstimates, but I still sometimes let the sheep overgraze (too much time for the available forage, so they chew the plants down too far for quick pasture recovery) or undergraze (too much area for the number of sheep, so that they start to eat selectively, overgrazing their favorites and ignoring the plants they like less, the all ice cream and no broccoli approach).

This morning, I erred a bit on the side of overgrazing, leaving the sheep a few hours longer in their overnight section than I should have. Aside from a few mature grass stems that they disdain, they had eaten everything down to about 4 inches.

They get very antsy as they sense that I’m about to let them move to the new section. I have the electricity turned off to the fence at this point so I can open a section without getting zapped, and I’m afraid that the sheep are starting to figure out when the fence is electrified and not. I worry that one day they’ll just push their way to freedom if I don’t move them quickly enough. Bravo and Cleo were leading the charge this afternoon.

And once the sheep are in the new grass, all the tension disappears.

____________________

*While the number of sheep is constant, their consumption of forage really isn’t. As the lambs grow, their rumens start to develop and they start eating grass in addition to milk. And the ewes’ lactation volume changes as the lambs grow (peaking around 45-60 days after birth), so their nutritional needs change accordingly. All the variables are in flux.